The Separate System

The Separate System

Two screen installation & single screen installation, 23 minutes, 2017/18

With kind support from:

Film festival selection for competitive international shorts:

The Separate System

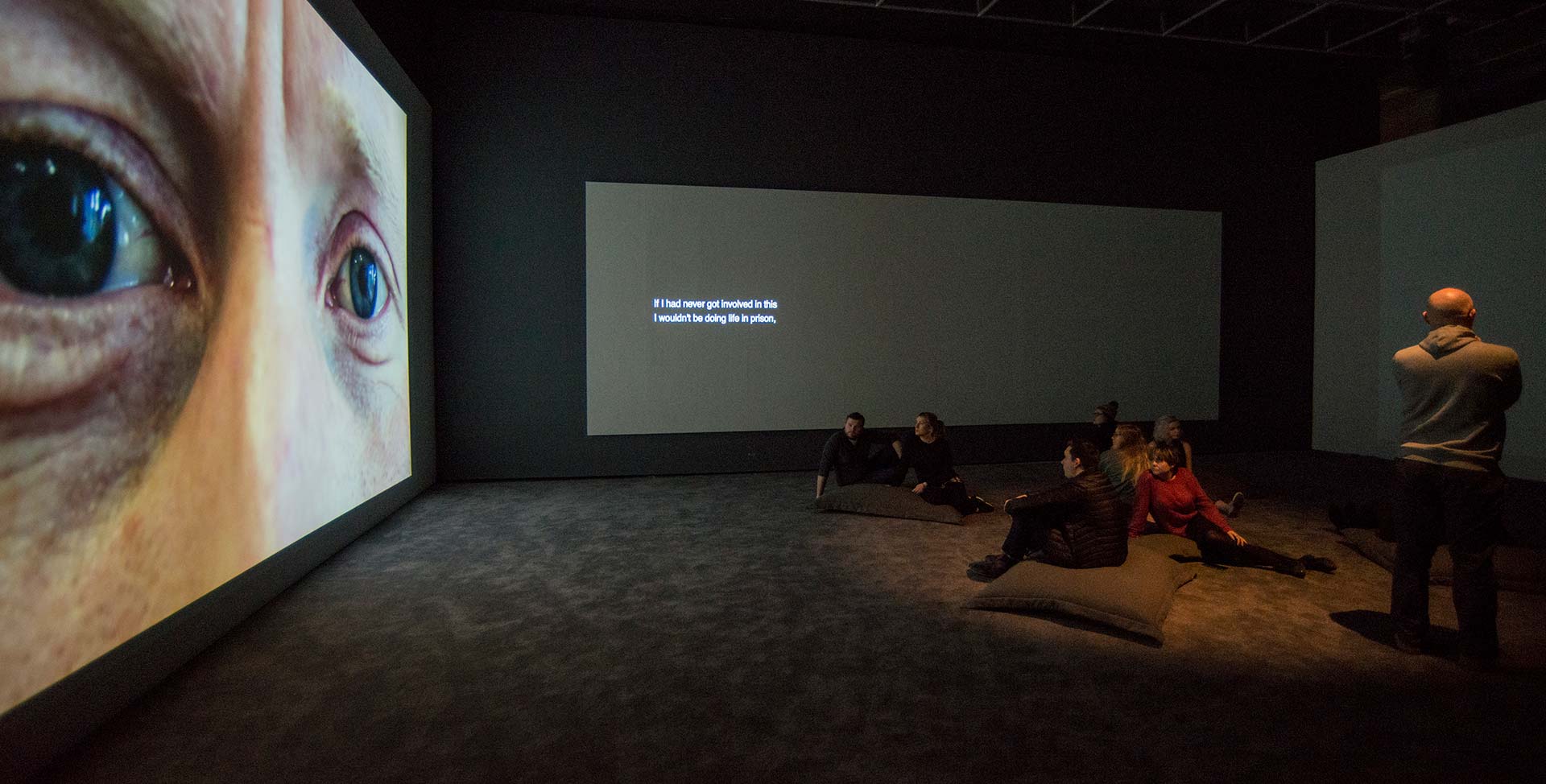

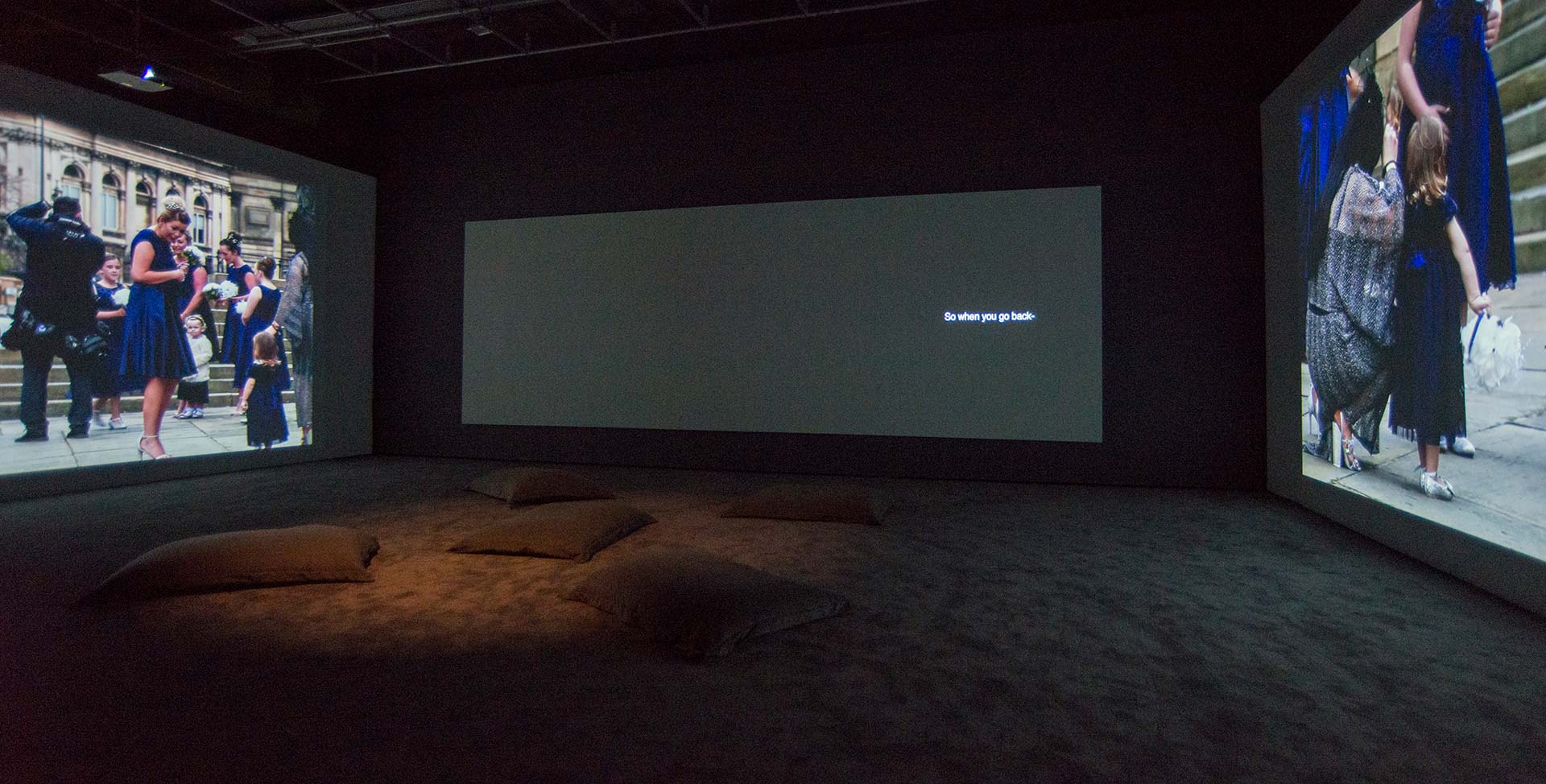

The Separate System (2017/18) is a collaborative commission facilitated by FACT’s Veterans in Practice programme, produced by veterans through workshops at HMP Liverpool and HMP Altcourse with artist Katie Davies. Taking the form of both a single channel cinematic film and a two-screen immersive installation, the piece explores the distinct, yet interconnected, spaces of the military, custody and ‘civilian’ life. Exploring these spaces and the experiences within them through the notion of work, an everyday activity that unites these worlds and is familiar to us all, the film communicates what we, as a civilian audience, do not understand about the unique set of relations, actions and responsibilities held by the individuals within these spaces.

Review of The Separate System for Modern Times Review: The European Documentary Magazine.

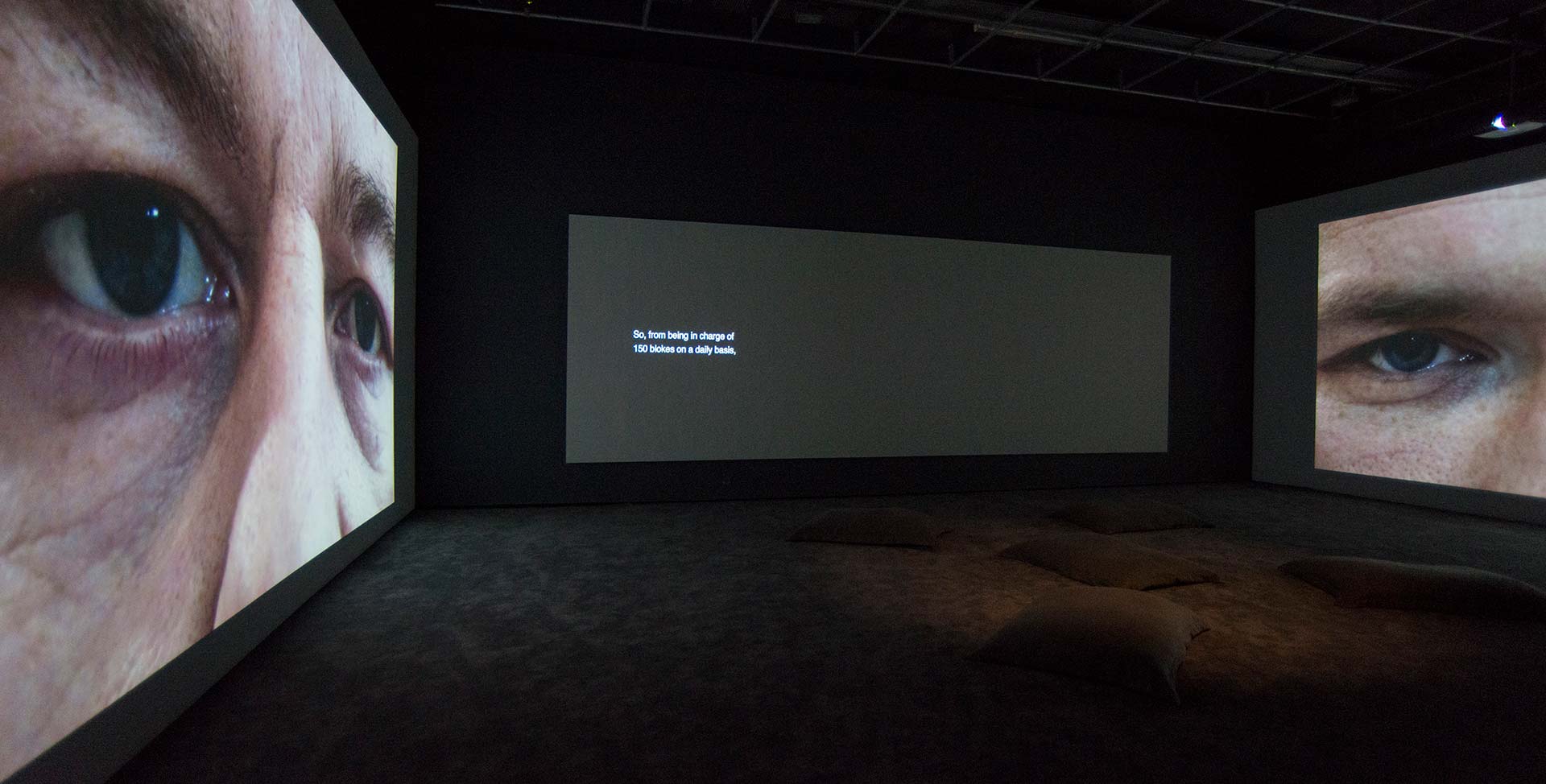

Installation text, FACT, 2018, Ellen WilkinsonThe Separate System amplifies quiet voices speaking serious words. The voices are those of armed forces veterans who are now in prison; voices rarely – if ever – heard. Each man, confined to a cell for most of the day, is given space: the space to speak. Their voices compete with the insistent background noise of stiff shoes on lino-covered floors, walkie-talkies crackling on and off, keys wriggling into locks, the groans and whines of metal doors in need of oil; reminders that prison is never silent. Each man tells a story only he can. Some are telling them aloud for the first time.

Veterans in prison occupy a unique set of spaces and identities – those of military, custody and civilian life – that are invisible to most of us. As one veteran describes the bombing of a market, we watch shoppers strolling through Ropewalks. The point is more than that market, in Baghdad or Helmand Province, could be here (and it is notable that no warzone is identified by name in this film, only by inference). We see Liverpudlians going about their lives, inhabiting public spaces and doing everyday things. Members of the armed forces define such ordinary places and activities as ‘civilian’ and in this definition is a sense of otherness. We hear veterans describing the difficulties of finding houses and jobs, dealing with neighbours’ intrusive questions, transferring their military skills into civilian life. While most of us will consider such tasks to be simple facts of ‘living in the real world’, there are probably few things as real as being on a missile-struck ship or possessing a level of responsibility that can ultimately save or end lives.

The architecture of power and control is a central protagonist in the film. The camera pans down glossy, pale institutional corridors, and along the prison’s taciturn perimeter walls. We see wedding guests posing for photographs outside St George’s Hall (the former home of Crown and Civil courts and now a concert, event and conference venue). Confetti clouds dance on its steps, which rise to the stone feet of imposing neo-classical columns. Across Britain, town and city centres are scattered with docile stone lions, elevated Dukes and Generals poised for victory, bronze Queens and Kings embalmed with arsenic-green patinas. They are part of the stories we tell ourselves as a society, which celebrate and idealise long-forgotten imperial glories and sanitise the horrors of war. “Look over here!” they cry, encouraging a form of collective self-distraction, as mythologies of the past obscure the realities of the present.

The men in this film have all experienced combat, yet they seem far removed from the smiling Second World War veterans selling poppies every November. In the act of public remembrance, the soldiers of now are less visible than those who fought in a war that has little in common with the conflicts of recent decades. While some war veterans can be celebrated as heroes, they must fulfil a nuanced and unspoken set of criteria. The heroic soldier is singled out as a ‘they’, a person apart from the mass of ordinary people. The incarcerated person is also a ‘they’, separated from the rest of ‘us’. Veterans in prison are even greater outsiders in the conversation of national remembrance; they are people we forget.

If we accept the notion that the military and prison systems act broadly in the public good, why are neither considered part of public space? Despite 24-hour rolling news, we see little of the realities of wars that happen ‘over there’, in places that remain distant and abstract. Prisons are also places out of sight, hidden behind physical and psychological walls. As a society, what is our responsibility for these spaces? Rather than answering this question from her own point of view, Davies shares the filming and editing processes with the prisoners that appear in The Separate System, and it is their words and perspectives that expose the many paradoxes of the often-invisible and highly complex systems that govern us all.

Conflicting expectations can create veteran-shaped crevices between military and public lives: being trained to kill but expected to behave – perhaps even to be a role model – on leave; being actively encouraged to settle internal-battalion grievances in the boxing ring (“that can’t happen in any other workplace,” notes one veteran), but being imprisoned for throwing a punch in the street; being sentenced not only for your crime, but for the training you received in your previous job: “the judge said that he expected more from a member of Her Majesty’s Armed Forces and that I had used the tools of my trade,” says one former soldier.

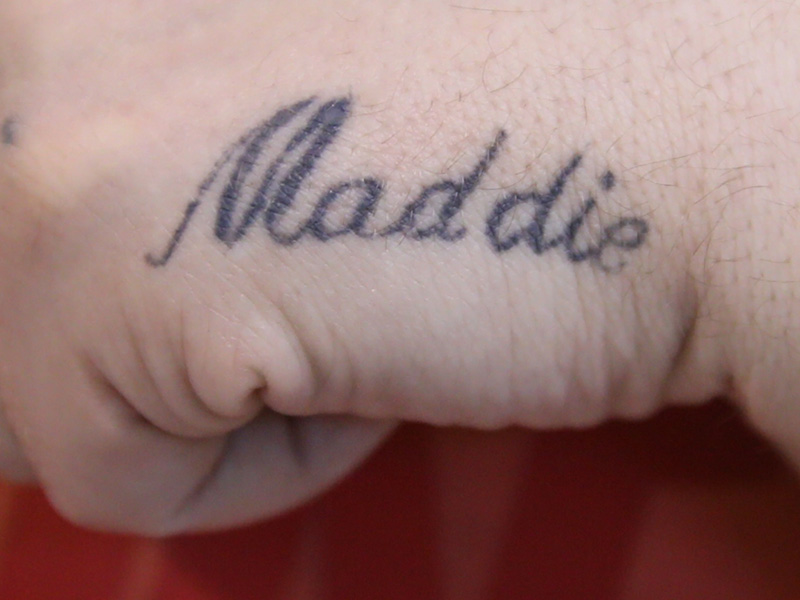

Of course, these men have committed crimes and one inmate tells us, “I don’t want people watching the film to think that I don’t deserve to be in here.” While we are left to assume that the justice system has performed its function in trying and sentencing them, their specific offences are not stated. In part, the film’s compassion lies in its removal of our inclination to judge these men solely on their crimes.

Some freedoms are voluntarily given up on joining the armed forces, and others forcibly and intentionally removed through incarceration. The Separate System is a powerful appeal that the voices of veterans should not be silenced when they are imprisoned. The term ‘veteran’ is defined not only as an ex-service person, but as someone with long experience in a particular field. From these men’s experiences there is much for the rest of us to learn.

"Davies captures the paradox of men who work in factories in jail to make objects that enable mobility by showing the moving parts; wheels in office furniture and tyres on automobiles. The film is revelatory but refuses to adopt a judgmental lens, making use of street scenes where individuals are granted freedom of movement to show the stark contrast between state imprisonment and what we perceive as social freedom"Tara Judah, Sense of Cinema, June, 2017

"Doing one’s duty, running errands, the system of military service, everyday and office life and family must be managed. Soldiers take responsibility for others; when their relationships fail, however, they are left alone: the detained former soldiers are sentenced and locked away. They know for what but not why. Because their punishment therefore stands for society’s flight into perplexity, the latter severs all ties with the people in question. This film gives a voice to these soldiers, talks about its impressive subject in rough recordings and harmonious, precisely filmed images. The hand-written notes that serve as breaks condense the detainees’ misery, work with the visual level to make their appeals of rage and loss directly to us, the community.

That meaning has become empty becomes emblematic at the end of this powerful and relevant work. Liverpool FC, their club, emerges as the great unifier of this community – but its familiar hymn, “You’ll never walk alone” which is thus implied reinforces the ambiguity of the former soldiers’ situation. Their lives are embedded in a close and separate system of society. The space of guilt widens, addressing issues of violence and society and what constitutes humanity by motive and identity."Statement from the Ecumenical Jury of Oberhausen International Film Festival, 2017

Awarded the Special Mention of the Ecumenical Jury, 2017

The Separate System

Awarded a Special Mention of the Ecumenical Jury, Oberhausen International Film Festival, 2017

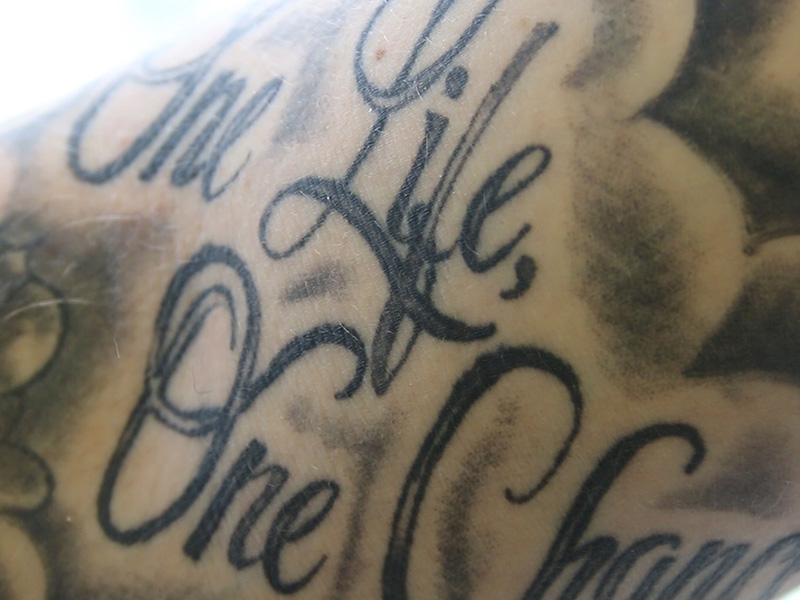

The Separate System

2017, HD still

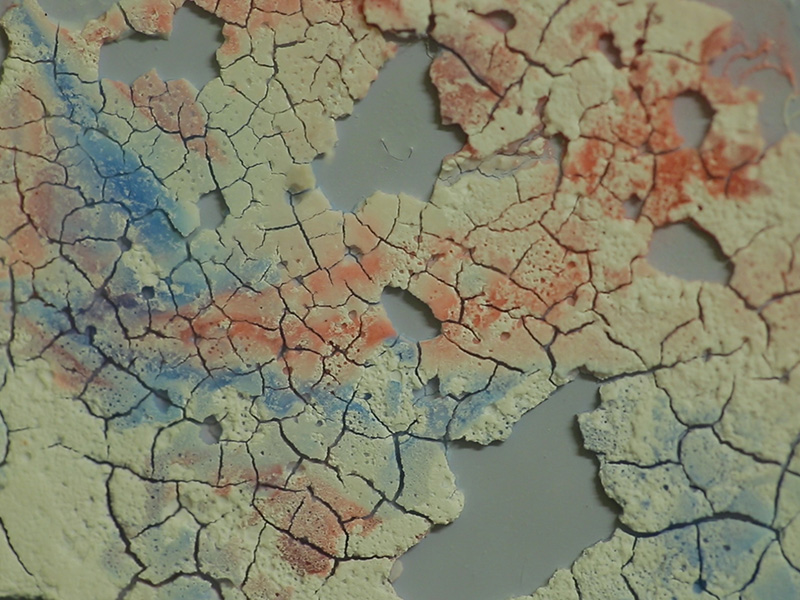

The Separate System

2017, HD still

The Separate System

2017, HD still

The Separate System

2017, HD still

The Separate System

2017, HD still

The Separate System

2017, HD still

The Separate System

2017, HD still

The Separate System

2017, HD still

The Separate System

2017, HD still